At NeurIPS 2025 in San Diego, we will be presenting our paper on geometric algorithms for neural combinatorial optimization. I will provide a brief summary of the paper and the main idea behind it. Before I continue, it may be helpful to read this blog post where I discuss some of the background and motivation behind the use of extensions for combinatorial optimization with neural networks.

Learning with extensions: background

First, let’s quickly summarize what an extension is and how it can be used to solve combinatorial optimization problems with neural nets. Assume that we have a function \(f: 2^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) whose input is any subset of \(n\) items. We can view the domain of \(f\) as the space of n-dimensional binary vectors, i.e., \(f: \{0,1\}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\). I’m overloading notation here to emphasize that the inputs of this function are discrete, however the outputs are allowed to be continuous. Throughout the text I will be using notation for sets and binary vectors interchangeably for \(f\).

In general, many well known combinatorial optimization problems will be framed as minimization (or maximization) over a feasible (sub)set of a ground set, i.e., we are looking for a set \(S \subseteq V\) which is typically represented by a vector \(\mathbf{1}_{S} \in \{0,1\}^n\) that minimizes the function \(f\). So we write

\(\min_{S} f(S), \; \text{ subject to } S \in \Omega\),

where \(\Omega\) is the feasible set.

Since we have a discrete (potentially black-box) function \(f\), a generally applicable strategy here would be to use reinforcement learning. For example, in a simple RL approach we would parametrize a distribution \(\mathcal{D}\) over sets with a neural network. Then we would sample from that distribution to stochastically estimate \(\mathbb{E}_{S \sim \mathcal{D}}[f(S)]\) and then update the parameters of the network with the log-derivative trick so that they optimize the \(\mathbb{E}_{S \sim \mathcal{D}}[f(S)]\). To deal with the constraints, we could customize the reward in a way that penalizes infeasible samples, or we could use a custom sampling strategy that prioritizes feasible samples.

Extensions provide an alternative path towards resolving this. As we saw previously, neural extensions essentially allow us to parametrize the distribution \(\mathcal{D}\) in a way that enables exact and differentiable evaluation of \(\mathbb{E}_{S \sim \mathcal{D}}[f(S)]\), which then allows us to backpropagate. So given a discrete function \(f\), its neural extension is simply a new (almost everywhere) differentiable function \(\mathfrak{F}: [0,1]^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) which extends the discrete domain of the original function to a continuous domain.

Different extensions can be obtained from different ways of constructing \(\mathcal{D}\). Given an input instance, suppose \(\mathbf{x} \in [0,1]^n\) is the output of the neural network on that instance. For example, the instance could be a graph and the neural network could be a Graph Neural Network. The key ingredient for constructing extension is to obtain from \(\mathbf{x}\) a distribution \(\mathcal{D}_x\) that consists of sets \(S_1, S_2, \dots, S_m\) and corresponding probabilities for each set \(p_\mathbf{x}(S_1),p_\mathbf{x}(S_2), \dots, p_\mathbf{x}(S_m)\) such that \(\mathbf{x}= \sum_{i=1}^m p_\mathbf{x}(S_i) \mathbf{1}_{S_{i}}\). Then the extension will be defined as

\(\mathfrak{F}(\mathbf{x}) \triangleq \mathbb{E}_{S \sim \mathcal{D}_\mathbf{x}}[f(S)]\).

We also have the following useful expression for evaluating the extension

\(\mathbb{E}_{S \sim \mathcal{D}_\mathbf{x}}[f(S)] = \sum_{i=1}^m p_\mathbf{x}(S_i) f(S_i)\).

Extensions via geometric algorithms

From the original paper already, it was apparent that one could naturally incorporate constraints into the extensions if one could find a way to build a distribution \(\mathcal{D}_\mathbf{x}\) such that \(S_i \in \Omega\) for all \(S_i\) in the support of \(\mathcal{D}_\mathbf{x}\). We did provide an example for a specific constraint but what wasn’t clear is the following question: Is there a general strategy for constructing extensions with support only on feasible sets? The answer, for a large class of problems, is yes. We propose a general decomposition algorithm that can generate sets and corresponding probabilities. We then have the following theorem:

There exists a polynomial-time algorithm that for any well-described polytope \(\mathcal{P}\) given by a strong optimization oracle, for any rational vector \(\mathbf{x}\), finds vertex-probability pairs \(p_{\mathbf{x}_t}(S_t), \mathbf{1}_{S_t}\) for \(t=0,1, \dots, n-1\) such that \(\mathbf{x}= \sum_{t=0}^{n-1} p_{\mathbf{x}_{t}}(S_t) \mathbf{1}_{S_t}\) and all \(p_{\mathbf{x}_t}(S_t)\) are almost everywhere differentiable functions of \(\mathbf{x}\).

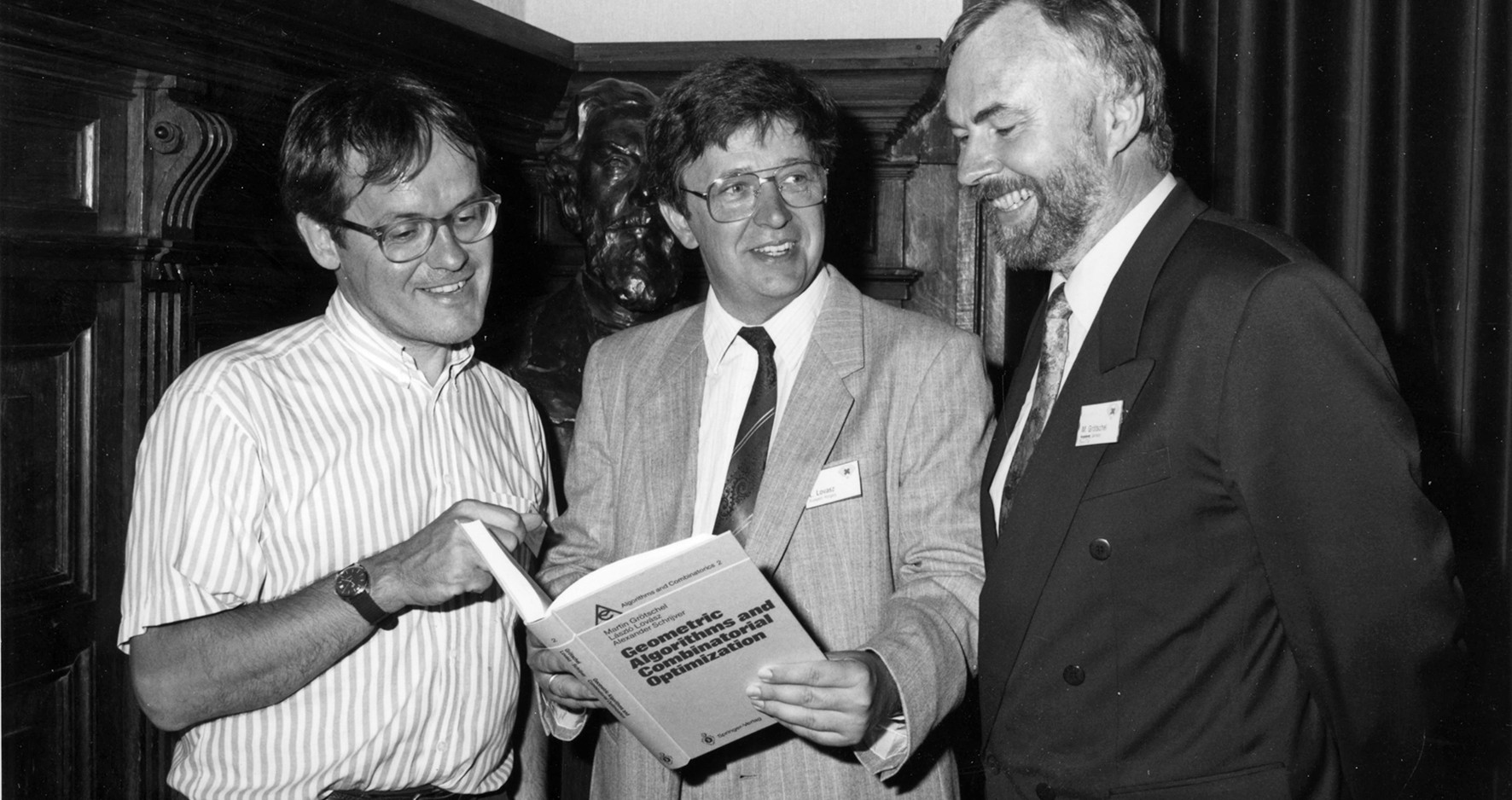

The theorem relies on an algorithmic version of the Carathéodory theorem by Martin Grötschel, László Lovász, and Alexander Schrijver (GLS decomposition), that appears in their book “Geometric Algorithms and Combinatorial Optimization”.

Briefly, we first define a polytope whose corners are all the feasible sets \(S \in \Omega\). Then, if there is an oracle for linear optimization on the polytope, such an extension can be constructed. To do so, given any interior point \(\mathbf{x}\) in the polytope, we algorithmically construct its Carathéodory decomposition as follows.

- Set \(\mathbf{1}_{S_i} \leftarrow \text{argmax}_{\mathbf{c \in \mathcal{P}}}\mathbf{c}^\top \mathbf{x}\)

- Fire a ray starting from \(\mathbf{1}_{S_i}\) that passes through \(\mathbf{x}\).

- Compute its intersection \(\mathbf{x'}\) with the boundary of the polytope.

- Clearly, \(\mathbf{x}\) is a point in the line segment whose endpoints are \(\mathbf{1}_{S_i}\) and \(\mathbf{x}'\). It is therefore a convex combination of the two.

- Set \(\mathbf{x} \leftarrow \mathbf{x'}\) and repeat from step 1.

By the GLS decomposition, this process will terminate in at most \(n+1\) steps. A key part of the theorem is to show that that the coefficients forming the convex combinations at each iteration of the GLS decomposition are (almost everywhere) differentiable functions of \(\mathbf{x}\) at each step, which allows us to backpropagate through the extension.

Our theorem is applicable to any feasible set polytope that admits an efficient linear optimization oracle. This includes optimization problems cardinality constraints, matroid constraints, and permutations. In the paper we provide worked out examples for the decompositions of cardinality constraints, spanning trees, and independent sets. The independent set polytope does not admit a polytime oracle for linear optimization but we discuss how one could work around this issue in cases where such an oracle is not available.

It is important to note that hard combinatorial problems can often be reformulated in terms of polytopes that admit linear optimization oracles . For example, the Travelling Salesperson Problem (TSP) can be viewed as a linear optimization problem over the TSP polytope but it can also be viewed as quadratic optimization over a permutation polytope. That permutation polytope (Birkhoff Polytope) admits a fast oracle for its linear optimization problem. In that case, the TSP problem would be solved by producing an extension of the quadratic objective over the feasible set of permutations. This significantly improves the applicability of our approach.

Finally, our proposed decomposition algorithm is more general than the GLS decomposition since it allows for approximate versions of the Carathéodory decomposition (Proposition 4.2 in the paper) . We provide an example of such a decomposition which we were able to use in our experiments to improve results on the maximum coverage problem.